Platanisteia is a small, semi-mountainous community in Limassol, just a few minutes from Pissouri. When it was abandoned by its Turkish-Cypriot inhabitants, the village became deserted, with most of its homes left in disrepair. This was the state in which Hambis Tsaggaris, known today as Hambis the Printmaker, found the village upon his arrival in 1988. Despite this, he was able to see beyond the weeds and the ruins, and envision the space which he had been searching for in order to create his artistic sanctuary.

Today, the complex of stone-built houses that Hambis restored has become a one-of-its-kind cultural center, complete with a workshop and a printmaking museum, placing the forgotten village firmly on the arts and culture map. Having managed to not only restore the one-time ruins and create a true oasis from scratch (both metaphorically and literally, considering the entire area is now blooming with greenery), Hambis is considered by many to be a fighter. After all, he has enabled his creation to grow and flourish in the face of a multitude of threats, and despite having received practically no outside support.

Hambis is no stranger to a life of struggle. After fleeing Kontea as a refugee in 1974, he lived in Nicosia for many years, writing about the island’s cultural activities for ‘Haravgi’ newspaper. Coming from a poor, farming family, Hambis had been both a farmer and a produce salesman in his lifetime, and had also worked in construction during his time at school and in the military.

The current image of the Museum bears no resemblance to the image of the ruins of the abandoned houses, the renovation of which Hambis undertook in 1988.

Despite this, Hambis was always an artist at heart, and this was something that never wavered with time. A man of great creativity, Hambis had followed his passion for printmaking (an art form that was little known on the island at the time) with such fervor that he was able to create from scratch an enviable space in the forgotten village of Platanisteia; a space that would allow visitors from all of Cyprus and beyond to discover his art. And so, this isolated little village of Limassol is now a pole of attraction for thousands of people every year, hosting works of inestimable value and inspiring people from all walks of life to chase their dreams and create.

The before and after of the many decades it took for the Printmaking School and Museum to become a reality says a lot about Hambis’ role in this process.

Hambis’ criteria for the path he was to take in life was never securing an income or financial security, but rather, to be able to express himself, and create something that would nourish his soul.

“I have never, nor will I ever, have much money. Money is not something that has value for me, it is fleeting, like the wind. What is valuable is what is inside of you.”

More than just a line, this belief reflects Hambis’ overall attitude to life, and it is this mindset that has allowed him to pour his soul into all that he does and overcome difficulties and obstacles in order to turn his dreams into reality.

“Normally, I would have gone to university in 1966, but due to a lack of money, I didn’t do so until 1976, when I already had 2 children,” he explains. He eventually managed to undertake 6 years of studies in Fine Arts in Moscow. And thus, at age 35, he began a whole new life, armed with the assurance of a man who is confident in both his art and his own abilities.

The old, stone-built houses, which had fallen to disrepair after many years of abandonment had been restored to their original form, revealing elements that were unrecognizable even to their original Turkish Cypriot owners, once they visited them in their restored form, such as the old range (fireplace).

In a time of such poverty, how easy was it to have a family while at the same time attending university?

The easiest part was starting a family. Life was different then. We didn’t care about the issues that people take into consideration today before starting a family. People had a different thought process then, unlike today, when you have all these things plaguing your mind before you get married and have children. Today, you allow the years to pass you by, weighing your options, counting one thing or another. Myself, I’m happy that I have a grandson who is already in the army.

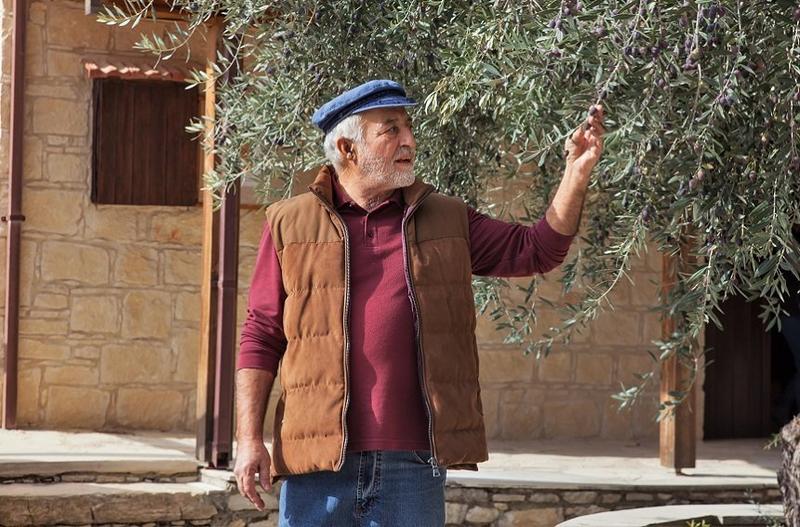

Aside from the restored buildings, the flowers and trees in the garden are also a dominant presence in the area. The dry land has been replaced by a green courtyard, flooded with the scents and colors of Cyprus flora.

How did you end up in Platanisteia?

The entire time I was in Nicosia I felt like I was drowning, and I could never find time to work on my printmaking. I returned to the non-occupied half of Cyprus, to an area where there were Turkish Cypriot villages, as this was the only way I could obtain a roof over my head as a refugee. When I came here, most of the houses were used as animal enclosures, with people living in makeshift homes in between the animals. I ended up up living in one such animal pen myself.

“The water was scarce and I didn’t even have my own water tank. In the early years, the village muhtar would open the tank and offer water with a dropper. I wondered what I could plant that wouldn’t dry out and I decided to ‘plant’ rocks. These were the first ‘flowers’ of the garden, and they have been standing for 28 years,” says Hambis, presenting the first of the visual changes he made to his garden.

The house I requested was used to shelter 2 bulls, and their owner had threatened me, because he was going to have to move his animals. When I began fixing up the space, however, everyone pitied me, even those who did not like me. First, I fixed up the little house in the back, so that I would have somewhere to live. I did not have electricity, or water, or anything. I spent 6 months living with the light of an oil lamp.

My happiest moment was in 1993, when I was creating ‘The Prince of Venice.’ I was completely alone, with a lit fireplace, a bottle of zivania, and a handful of raisins.

At the time, I realized I had never before experienced such happiness. I was very happy though. I would gladly relive it. And here I am, 30 years later, still working to create something new every day.

Has this been your only work since then?

No. I also worked in education for 21 years. I was a graphic arts teacher at the Limassol Technical School until I retired in 2008.

Wasn’t the daily Platanisteia – Limassol route tiring for you?

It never tired me. Living here, in the village, is very restful. I liked my work at the Technical School, however, and interacting with the students. It’s very touching to see how many of them often come to visit me here.

When did the Ministry approach you?

There was a period, in 2000, when the Director of Cultural Services at the time had given his support to the School. We received no help, however, for the remainder of the years. Even in 2008, when the Museum was inaugurated, the only aid we received was from sponsors and donations from people who bought prints of my work that were sold for this purpose.

“Every crack is a light in the darkness”, was a saying of Hambis’ great teacher, the top printmaker Tassos from Greece. So, he makes this clear: “I didn’t start off trying to create a garden for myself, but rather a place for people to visit, and this is why I put benches everywhere, so that visitors who come for performances will have a place to sit”.

The names of these approximately 200 donors are today honored on a plaque at the entrance of the Museum. Fortunately, once our efforts were underway, we also received support from the Hellenic Bank, whose enlightened team had an affinity with the arts, and helped us turn our vision into a reality.

Is there a lack of museums in Cyprus?

It is not museums we are lacking, but rather the culture of visiting museums. I personally do not blame anyone for not knowing about printmaking, because most likely they were simply never given the opportunity to learn about it. A lot has changed since we established the Museum and the School. In 1982, not many people knew what a printmaker was, though everyone knew what a counterfeiter was (laughs).

Every corner of the space is decorated with carved stones, while at the entrance of his own home, Hambis has created a metallic mesh that prominently displays the names of the great artists whom he considers to be his masters.

Today, all schools teach students about printmaking, and we have even reached a point where we are now organizing the Youth Printmaking Biennale in cooperation with the Ministry of Education for the second year in a row. This would never have happened if this space had not been created. This would never have happened if this space had not been created, if it had not opened its doors to the public in order to pass on the message that art and culture are an experience rather than a mere theory.

“Nothing is difficult if you love it. Finding the way to build this space was not easy, and neither is purchasing works of great artists every now and then to enrich the Museum’s collection. But you can do anything if you love it enough.”

It took him 30 years to turn his dream into a reality, but to this day, Hambis has never stopped dreaming and planning for the future. He is a giver, and the more he gives, the more inspired he is to create and share even more. As he narrates all his life’s events over the years, he does not spend time on the things or the people that made his life bitter or difficult. And though 2018 was a tough year for him, with the village authorities threatening the closure of his Museum and School, he chooses to focus only on the people who have come to love him and his work, and the many whom have benefited from it.

Various events regularly take place in the Museum’s area, attracting many of visitors to the village, in addition to those who already visit for the exhibits. “I always wanted people to come here, I wanted them to get to know and love printmaking, culture and the arts through this space. And I achieved that, I think”, Hambis says, but he adds “I do have 1 complaint: with all these people coming and going, I have trouble finding the peace and quiet I need to create. And so, I found a new place to hide away, but I am not revealing it to anyone!”.

The success of his venture is fueled by the love, faith and devotion he has poured into it. As the inscription welcoming visitors to the Museum reads, nothing makes him happier than giving back, and this fact has relieved him of the concerns and fears that usually inhibit the plans of those who have ideas but never act upon them. If there ever was a reason for such a tribute by All About Limassol (the Official Guide of Limassol) on Hambis and his life’s work, it is because of what visitors encounter upon entering Platanisteia. Even before coming across the sign that welcomes them to the village, visitors will see the sign for the only Printmaking School and Museum on the island and, once they are in the village, they are welcomed by a picturesque and well-maintained square, which was made possible directly as a result of the existence of this space. Beyond being a great artist, Hambis the printmaker is also a man who embodies what it means to bring true value to a place.